Sites of Wonder: Encounters with our Tiffany Windows, Part II

Join me before a gorgeous window that “highlights” illumination in an intriguing way!

This window illustrates a biblical passage (John 3:1-21) about an exchange between Jesus and Nicodemus, a prominent member of the Sanhedrin (the Jewish supreme council or tribunal) and a senior intellectual. Convinced of the young teacher’s message and mission, he seeks to probe deeper. He approaches Jesus at night for secrecy, given the risk of associating with the worrisome Nazarene.

Tiffany Studios, Christ and Nicodemus, 1911, photo by Kristian Bjornstad

The window’s design focuses on Jesus’ response to Nicodemus’ query: what do you mean by ‘born again?’ Jesus explains he means rebirth through water and the Spirit—baptism—as the key to reach the kingdom of God.

There is no inscription to provide that message. Instead, the image gives us an encounter with extraordinary visual and psychological force. We see an intense dialogue between two worthies of different age and status. Their mutual gaze connects them as much as their poses. The handsome, mature Nicodemus, supported by a cane, listens intently, leaning towards Jesus who touches his shoulder while gesturing and speaking. The glowing lamp, the brightest element of the image, is critical. Narratively, it indicates Nicodemus’ nighttime visit. Symbolically, it suggests his enlightenment with the exchange. Its rays wash over both men from head to toe, uniting them The setting at the entrance of a simple yet dignified building amidst lush plants, backed by soaring peaks, lends a grandeur that emphasizes the meeting’s importance.

Vivid and flickering, color and light suggest falling dusk more than settled night. Without upstaging the expressive heads and hands in opaque paint, Tiffany Studio’s hallmark translucent opalescent glass provides both dazzling visual effects and naturalism (veined stone, stripes, spots, light, and shadows).

Set on the lower register of the nave’s south wall, this window with life-size figures capitalizes on changing natural daylight to bring an image of searching dialogue, of growing inner illumination, to radiant life in our space.

The Tiffany Census records six variants of this design, but not St. Stephen’s. The earliest among the recorded variants, at the Third Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh, dates from 1903. Some are attributed to Tiffany’s head designer Frederick Wilson; the similarity of St. Stephen’s version to these suggests it too may derive from Wilson’s design. Landscape elements may be by Tiffany’s top specialist, Agnes Fairchild Northrop. The power of St. Stephen’s version is due also to the artist-artisans who adapted the design in glass.

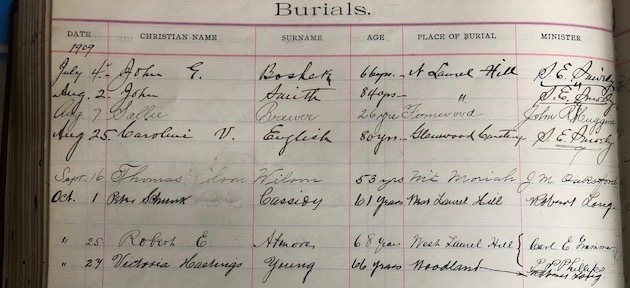

In June 1911, St. Stephen’s vestry approved—in principle—a window proposed as a memorial to Robert E. Atmore, (d. 1909) by his widow, son, and three daughters. The appointed committee accepted Tiffany’s submitted design for this window the following October, giving us insight into the church’s controls on decoration at the time.

Robert Atmore, I found, gives us an intriguing perspective on city and church history. He ran a successful business in South Philadelphia at 110 Tasker Street established by his father, the first in the US to produce mincemeat and plum puddings. According to his obituary he was also an engaged, usually anonymous philanthropist--especially to social services for the urban poor. He actively served as well as gave money. He was vestryman for an Episcopal church founded in 1847, by a white congregant at St. Paul’s Church, for poor blacks also in South Philadelphia (8th and Bainbridge): the Church of the Crucifixion. Its rector—the pioneering black social reformer, The Rev. Henry L. Phillips—assisted The Rev. Carl E. Grammer for Atmore’s funeral at St. Stephen’s. It is heartening to learn of this bond between two distinctive urban churches!

-Suzanne Glover Lindsay, St. Stephen’s historian and curator