Friday Anniversary Perspectives Opened Up Close: Worlds Within Our Floor Registers

Floor Register at St. Stephen’s

At St. Stephen’s, we usually look around and up at its compelling architecture and art. Yet over time I’ve noticed visitors who gather, in deep debate, looking down—at floor registers that pierce the worn carpet. What I overheard thrilled me: new perspectives and questions. Other discussions suggested that visitors might come forth with revealing insights. They were teaching us, opening up this world for us all.

Visitors moved me to re-focus just on the floor registers, which I’d preliminarily explored when I arrived in 2017.

Looking again and closely at these pieces last week, I found new thinking rose in response because I saw more this time. And new thinking led to new research, with new results and questions.

Some insights were historical, and what a history. These registers (vent covers with movable baffles to control air flow) mark this church as a progressive American enterprise for its time. The description appended to Bishop Hobart’s 1823 consecration sermon emphasizes that the new church offered, as part of its modern American identity, interior heat piped from a “Lehigh coal furnace built in the cellar.” That’s an advanced amenity that gave this church an edge among its peers.

Detail

Thanks to this specification, St. Stephen’s participated in the area’s energetic new development. The church’s architect William Strickland, also an engineer, included a furnace that was built by an influential new (1818) regional company, soon called the Lehigh Coal Mining Company, and fueled by the company’s anthracite coal found recently nearby. That coal soon traveled to Philadelphia down new canals and railroads that bypassed the white water on the Lehigh and Delaware rivers. Strickland also worked for companies that built these transportation networks.

St. Stephen’s floor registers remained even as radiators were added. Why? Their strong presence says a lot. There’s even more up close.

For me, who cast bronze and iron in small screw and stove foundries, closely examining the metalwork opened new worlds.

The intricacy of the pierced design was clear even standing. Up close, I learned these were, like many admired examples of the period, cast-iron pieces with finished tops to gritty, lightly oxidized (rusted) elements. Their openwork pattern belies their strength. Some of the baffles still moved. Was the warm, even surface color due to exposure or added chemically?

Up close, these registers conjured the busy, smelly foundry and its myriad artisans. I imagined a model pressed into foundry sand to form the mold then, after the pour, the raw, cooled cast as it was removed, filed, and finished. I admiringly ran my fingers over the actual casts. I saw few casting flaws. Their excellent condition, despite sustained foot traffic, spoke legions.

There are several of this type, all subtly different, throughout Strickland’s original building and two in the Furness’ transept (now the Furness Burial Cloister).

I don’t know their dates yet but those within the 1878 Furness annex were likely added.

Center aisle with two floor registers (“borders” may be shadows cast by the pendants)

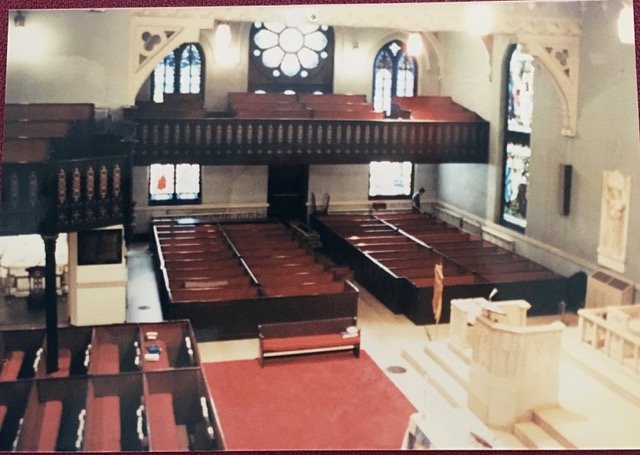

The spatial context of these floor registers today, however, is radically different from before. All were originally installed in aisles surrounding box pews that were removed c. 1989 to open the space. Two photographs of the pews still in place in the 1980s suggest how striking the decorative registers were in those defined rectilinear spaces, framed by dark, looming wood enclosures.

So many questions about the registers’ history and fabrication arose. I hope visitors can contribute here.

Chancel and Furness transept c. 1989 before the platform for performances was added

Yet, I’ve learned by listening, these iron registers, with their lively arabesque elements, appeal powerfully to the imagination in many directions. My favorite so far is how two black Muslim men responded to the register nearest the west entrance. One was sure he found messages in the pattern in the Arabic he learned as a child; what did he decide? I look and imagine, knowing the church speaks in many languages, like the rose window through composition, color, and emblems. It thrills me that St. Stephen’s speaks to those from different cultures and perspectives—some of whom share their experience here.

Whether intentionally “speaking,” providing private messages to individuals, or portals to wide-ranging contemplation, these floor registers invite us to look and open to what comes.

— Suzanne Glover Lindsay, St. Stephen’s historian and curator