Friday Anniversary Perspectives Opened Up Close: Meditations on a Severed Toe

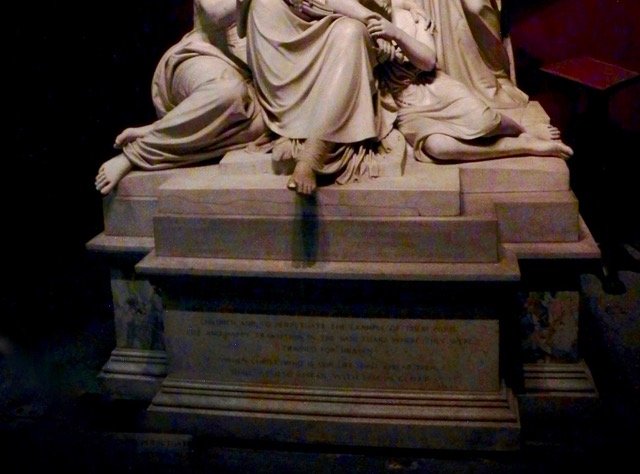

Detail, Steinhäuser Burd Children’s Memorial, 1852

A severed toe, which this photo documented soon after it occurred in October 2017, provided bittersweet evidence of a radical shift within the church. It witnessed how physically close we now come to what was intended as a supernatural vision to be experienced from afar, in a separate space, through gates and a barrier: the 1852 Burd Children’s Memorial that crowns the family burial vault beneath Richard Upjohn’s simple “chapel.”*

We, the public, were also supposed to see this compelling marble only from its “front,” as most of us do when in the nave today without the gates and barrier.

View in situ: Steinhäuser Burd Children’s Memorial

The chapel’s supernatural isolation ended when its side walls were pierced with doors into Frank Furness’ 1878 additions on each side. Congregants in the new transept to the east were invited to contemplate the sculpture, as we do now in the space’s new form, the Furness Burial Cloister.

Congregants could also travel THROUGH the chapel to the transept from Furness’ new 10th St. tiled annex entrance, as we can today, passing under the open stairwell of George Mason’s later Parish House. The view was and remains captivating.

The once-cloistered marble group was thus drawn into St. Stephen’s worship and everyday life.

Can you imagine, when first seen up close, the power of the sculpture’s sheer scale? Figures are life size; the group’s overall height on the base is about ten feet. Yet standing there, the dramatic silhouette of the angel’s outspread wings and the looming crucifix, against rich burgundy walls, gains touching nuance.

There, the children’s bare feet overhanging the base on three sides draw us, challenging the border between us and the supernatural. Their feet are so THERE, so human, so moving, so touchable.

Yet the sculptors took standard studio precautions with marble. Hidden when viewed frontally is a sturdy “bridge” (support) under the left foot that extends so far beyond the outermost base.

As St. Stephen’s fall season began in 2017, I, given my decades working with art, winced as I watched people flow past this huge vulnerable marble in a tight space—without a barrier. I soon found a glaring white loss on the projecting foot where the tip of the big toe had been. The missing fragment was also gone.

Until then the marble had been lucky: It lost only one finger and had two others reattached over time. Such a large sculpture with projecting, delicate elements is at risk at all stages. Imagine, once finished, the many steps to moving it from a Roman studio to its intended home in Philadelphia.

Yet damage to the toe hurt us all. The loss was likely caused by someone, who focused elsewhere, bumped the fragile extended foot in what had become a bottleneck in a major traffic artery. Yet the “wound,” still fresh, shines like a star, far and near. We wonder where the severed fragment is . . .

So consider the reinstated barrier an invitation to engage with the marble group mindfully. There, we repeat the experience of the sculptors in the studio and of many generations at St. Stephen’s who, approaching it with respect, found it enabling up close, exploring its hushed artistry and opening doors to reflection.

— Suzanne Glover Lindsay, St. Stephen’s historian and curator

*For more on the original project, click here.